18 Apr ‘And so is history made’: A Dialogue with North Carolina Maritime Historian and Author, Kevin Duffus

Kevin Duffus is a prolific author of multiple coastal North Carolina maritime history books and articles who is known to be reflective, a dogged researcher, and a man who has allowed curiosity to drive him to embrace and unravel mysteries. We asked Kevin—to whom writers, researchers, and readers owe a measure of debt—to allow us to shine a spotlight on his life. He willingly took the time to answer 25 questions. The insight he shares is invaluable.

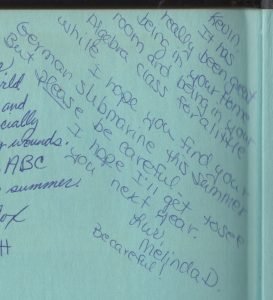

‘… I hope you find your German submarine this summer.’ This message was written in Kevin Duffus’s 1971 high school yearbook as he made plans to search for the U-352 off Cape Lookout, the location of which was then unknown. Photo courtesy of Kevin Duffus.

What inspired you to research and write about NC maritime history?

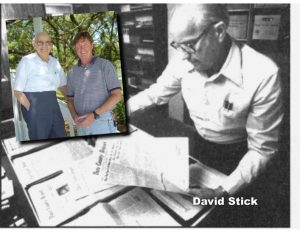

Not long after my family moved to eastern North Carolina in the 1960s, I found the book “Graveyard of the Atlantic” in the local library. As a 15-year-old, my imagination was captivated by David Stick’s history of shipwrecks and heroic rescues. That book led me to others, some non-fiction and some pseudo-histories like Ben Dixon MacNeill’s “The Hatterasman” and Charles Whedbee’s beloved books of Outer Banks legends. In time I learned about early explorers, pirates, wreckers, smugglers, lighthouses, U-boats, historical myths and mysteries. My fate was sealed, my future forged by an unbridled passion for the history of the North Carolina coast even though I later learned that not everything I had read was true.

I was especially fascinated by the reality that evidence of the past is all around us even if we don’t often see it. I began to explore. One teenaged expedition took me to Plum Point near Bath where the pirate Blackbeard purportedly lived. Holes in the ground suggested that I was too late if I had expected to find his long-lost treasure. Another exploration led me to discover the long-forgotten site of a Civil War skirmish on the north side of the Tar River.

Having earned my scuba diving certification at 17-years-old, my friends and I searched for the location, then unknown, of the German U-boat U-352 south of Cape Lookout. Despite failing on that mission, I soon after found, explored, and identified a sunken Confederate gunboat west of Washington near the Tar River.

A couple of years later I searched for and found the grave of Blackbeard’s mythical sister hidden in an inhospitable forest of tangled briars and weeds along the Tar River. But was she his sister? The dates on the gravestone said no. More historical disenchantments!

I realized that history is an inexhaustible wellspring of beguiling dramas and unsolved mysteries—not just because so much of our past has been forgotten or hasn’t been preserved in records, but because so much of our history is buried in myth and falsehoods.

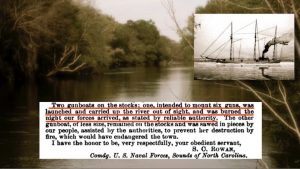

In 1972, Kevin Duffus and his high school friends found, explored and identified a 140-ft.-long sunken Macon-class Confederate gunboat in Chicod Creek between Greenville and Washington, NC. Graphic provided by Kevin Duffus.

For more than four centuries, extraordinary, notable, and improbable events of American maritime history have occurred on North Carolina’s coast. And, like the sun-bleached timbers of a once majestic ship decomposing into the sands, the true, accurate accounts of what took place there have blended with the fuzzy, faded memories of eyewitnesses who passed their stories down the generations. Historical truth has merged with the inevitable embellishments of storytelling; facts have been confused with literary inventions, mangled by poor scholarship, revised for political purposes or financial gain, cast away for versions more entertaining and popular. The result: fact and fiction, romance and reality, past and pop culture are woven together like a colorful but perplexing tapestry of time.

I’ve often wondered—can truth and legend be unwoven? Is it possible to identify and follow the threads of historical truth? Can longstanding mysteries be solved? That’s what has intrigued me and challenged me while researching and writing about the maritime history of North Carolina. But ultimately, what most excites me is the opportunity to explore untrodden historical territory, to add to our knowledge of our past, to introduce new or more refined facts, and to inspire current and future lovers of history.

How many books have you written and what are their titles?

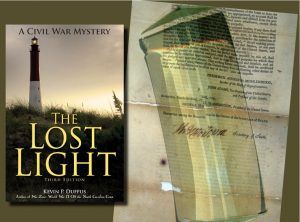

‘The Lost Light—A Civil War Mystery,’ third edition published in 2015, alongside an Act of Congress signed by Thomas Jefferson that had been used to wrap Fresnel lens prisms hidden in the NC Capitol in 1865. Graphic by Kevin Duffus.

I have written and published six books, all on the maritime history of the North Carolina coast. “The Lost Light—A Civil War Mystery” (2002) was the first and tells the parallel stories of the historic 1853 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Fresnel lens, how it disappeared during the Civil War, and how I found it after it was said to be lost by historians for 140 years.

Next, I published “Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks—An Illustrated Guide” (2006) which was intended to be a pictorial companion to David Stick’s seminal “Graveyard of the Atlantic” as well as a field guide to shipwreck remains that are sometimes visible to beachgoers.

Then, after many years of research and analysis, including a week-long visit to England and the British Archives, I published “The Last Days of Black Beard the Pirate” (2008), which is now in its fourth edition as I have never stopped researching the greatest pirate enigma in American history.

After producing a three-hour long documentary on German U-boats off the Outer Banks, I decided to publish a book on the same topic but extending it to the entire coast of North Carolina and “War Zone—World War II Off the North Carolina Coast” (2012) was the result.

In 2017, following a considerable period of research I wrote “The Story of Cape Fear and Bald Head Island” for, and with the support of, the Old Baldy Foundation. That book spans 500 years of American history.

Then, in 2018, for the centennial of the historic rescue of the survivors of the torpedoed British steam tanker MIRLO by the Chicamacomico Coast Guard Life-boat Station, I wrote “Into the Burning Sea—The 1918 Mirlo Rescue.”

Was there one book that was more difficult to research and write than another? If so, why?

My book, “The Story of Cape Fear and Bald Head Island” published in 2017, was the most difficult because it encompasses such widely varied maritime topics over five centuries of history—the earliest navigations and charting of the Carolina coast, 17th century efforts to explore and establish settlements along the Cape Fear River, pirates, lighthouses, lifesaving on Frying Pan Shoals, the Civil War and the Second World War, and many modern ill-fated efforts to develop Bald Head Island into a vacation destination. That book required every facet of my knowledge of maritime culture while testing my research skills, mental and physical endurance like no other book I have written. I am also proud of the fact that the book is full of groundbreaking historical facts as a result of my research.

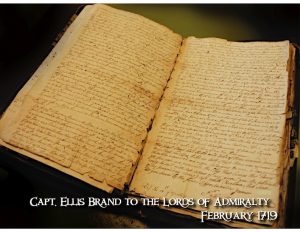

The original letter written in 1719 by Royal Navy captain Ellis Brand to the Lords of Admiralty detailing the expedition into North Carolina for the purpose of capturing or killing of the pirate Blackbeard. Within this letter found in the British Archives Kevin Duffus discovered previously unknown facts that significantly altered traditional interpretations of the Battle at Ocracoke. Photo by Kevin Duffus.

What about the research process do you like?

The hunt! The process is a search for treasure and always an adventure—a continuous roller coaster ride of twists and turns, surprises and disappointments. It is a search for lost facts, answers to riddles, missing pieces of a puzzle, and people from the past who witnessed momentous moments in history. On one hand, historical research can be fraught with anxiety, expense, inordinate amounts of time, frustration, disappointment, uncertainty, and occasional dead ends. On the other hand, for me, finding a groundbreaking lost fact in a faded, time-worn, original handwritten document is an exhilaration and a reward that makes all the difficulties worth it.

What are the challenges of the research process?

There are so many. Figuring out how and why established history is sometimes inaccurate, or entirely wrong, and correcting it, is one of the greater challenges for a research historian. So much of our past is a vast, inscrutable riddle—a jigsaw puzzle without all of the pieces and no box cover of the puzzle to help us reassemble the pieces correctly. Monolithic historical interpretations must be completely deconstructed through original research before the historian can begin to find the truth of history. Often it is more work than many people are willing to do.

Another pitfall that lies in the path of the diligent historical researcher is the underlying bias that is part of nearly all records. An example is the letter that Virginia’s Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood wrote in 1719 to one of the Lords Proprietors of the colony of North Carolina, in which Spotswood tried to justify his authority in directing an unprecedented armed incursion into his neighboring colony in order to capture or kill Blackbeard and his cohorts. Spotswood’s letter was biased, and I needed to understand why. By piecing together a forgotten political conspiracy using a variety of clues, I successfully deduced the real motive for capturing Blackbeard—the acquisition of evidence to trigger the overthrow of the proprietary government and restore Royal authority in North Carolina. The very same thing was occurring at the time in South Carolina. Political parties disillusioned with proprietary rule in both North Carolina and South Carolina sought ways to replace their governments. South Carolina succeeded in 1719; it took North Carolina another ten years to do so. Blackbeard, I concluded, was simply a pawn in a complicated game of colonial political chess. Over the years, enthralled scholars and writers, likely blinded by the glitz and excitement of swashbuckling pirate lore and the prospect of plundering the legends for book royalties, lost sight of the true story which I believe is far more fascinating.

Another challenge is not knowing where to look for the answer to a question. Fortunately, knowledgeable archivists are often able to help put the researcher on the right path—but not always.

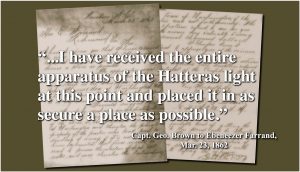

I have sometimes achieved success by being intuitive and willing to spend inordinate amounts of time searching in places others have ignored. As an example, against the advice of a senior archivist specializing in Civil War records at the National Archives who was adamant that I would not find what I was looking for, I discovered a letter from a Union general within a microfilm roll that revealed the remarkable story of how the pre-Civil War archives of the state of North Carolina—including original documents signed by Thomas Jefferson—had been used as packing paper for contraband lighthouse lenses. My discovery absolutely stunned George Stevenson, senior archivist at the North Carolina Archives, for he finally understood why many of those letters that were eventually returned to the state were so badly damaged.

Do you have any advice on researching for fledgling researchers?

Don’t ever give up. The answer is out there. And make friends with the archivists—their knowledge and assistance are invaluable.

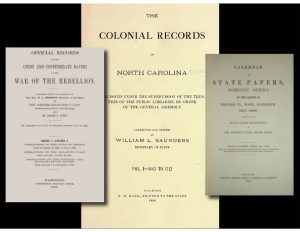

Considered by most historians to be primary sources are published compilations of official government papers like North Carolina’s Colonial Records, Britain’s Calendar of State Papers, and the Official Army and Naval Records of the War of the Rebellion but these sources often omit important information. Graphic provided by Kevin Duffus.

Is there something researchers must keep in mind?

Historical research is not simply reading a number of books and articles and then writing your own, nor is it a matter of relying solely on period published accounts like newspapers. Perhaps the most important bit of advice I can offer other researchers is to never depend on the work of others; do not accept their interpretations of period documents without reading them yourself.

Here’s an important lesson I’ve learned. Considered by most historians to be primary sources are published compilations of official government papers like North Carolina’s Colonial Records, Britain’s Calendar of State Papers, and the Official Army and Naval Records of the War of the Rebellion. More and more of these records are now accessible online. But, while convenient to access and easy to read compared to their handwritten sources, I tend to be rather wary of published abstracts because you never know what sort of critical information the editors have chosen to discard or failed to include. I would never have succeeded in establishing the brief piratical career of Bath’s representative to the colonial Assembly and founding patron of the state’s oldest surviving brick church, the cooper Edward Salter, had I relied entirely on the published abstract of his former captain’s deposition in the Calendar of State Papers—only within the original record did his name and occupation appear, the crucial key that unlocked a door to a closet full of revelations. Consequently, my visits to the archives are always more time consuming and tedious because I do my best to avoid indexes and abstracted records in favor of handwritten records for fear that many years ago some harried civil service clerk made a transcription error or entirely omitted something important.

But meticulous research of primary sources is only part of the equation in the process of historical writing. Rigorous analysis of historical research is every bit as important. Historical research typically answers the what, the where, the when, the how, and sometimes the who; but historical analysis provides the answers to the why. And it is beneath the why where the most fascinating secrets of history lie buried. Deducing why things happened is essential for a historian to interpret history fully and accurately.

Historical analysis, for me, provides the greatest challenge, and the most satisfaction. It is during those moments of revelation, after countless solitary hours of reading, parsing, and analyzing the facts, and following the long process of reflection, reasoning, and deduction, that with a lightning-bolt-like spontaneous flash of awareness, out of the murky mists of time, clarity and understanding emerge before the historian’s eyes.

How do you start the research process?

Research, for me, always begins with a question. How could the six-thousand pound, 12-foot-tall crown-glass Fresnel lens from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse have vanished into thin air during the Civil War? Why did U.S. Naval Intelligence at Norfolk violate the 3rd Geneva Convention by attempting to hypnotize and drug German POWs captured from a sunken U-boat off Cape Hatteras after they had survived floating on the ocean for 49 hours in the summer of ’42? Why did the Speaker of the House of North Carolina’s colonial Assembly nail himself inside the house containing the government’s records for 24-hours a few days after Christmas in 1718? Why were some of Blackbeard’s shipmates living long and productive lives many years after they had been “hanged” in Williamsburg? Where was the location of the weed-covered grave on Hatteras Island of one of America’s greatest and most heroic lifesavers of all time?

These are the sorts of quandaries that motivate me. I begin with a question and then I map out the various paths of research to explore where I may, or may not, find the answer. One step leads to another, one clue yields a half dozen new questions and new paths to explore. The process is seemingly endless. One book may require years of research and critical analysis of the evidence. At some point, I decide that I know enough and have sufficient data to begin writing.

What makes good writing or a good story?

Good historical writing places the reader on the edge of the action as an eyewitness to history as it was being made. The 19th century American historian Francis Parkman said: “Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. The narrator … must be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.” This has become an important facet of my writer’s creed. Another beacon of wisdom by which I try to steer my historical prose was expressed by David McCullough: “No harm’s done to history by making it something someone would want to read.” I hope, for my readers, I’ve made history compelling.

Researching North Carolina lighthouses at the National Archives, Washington, D.C. in 2016. Photo by Kevin Duffus.

Have you traveled to research?

To accomplish real primary source research—and I’m not talking about searching for information over the internet in the comfort of one’s home or office—the historian often must travel. The sacrifices, risks, and stress of archival research away from home are daunting. Research is costly, the hours long and exhausting, and the effort sometimes fruitless. It’s a gamble, especially without the financial backing of a grant, patron, or institution—in other words, on the researcher’s own dime.

Many times, at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., I have waited anxiously for record retrievals, pouring over hundreds of fragile, handwritten documents, sitting for hours on end in uncomfortable chairs without food or water, knowing that the costs are mounting as fast as the second hand of the clock on the wall turns. Of course, when you do find what you were looking for, or even something remarkable you weren’t looking for (that happens a lot), the euphoria is nearly narcotic.

In 2007, I experienced that sensation at the British Archives west of London while reading a letter from a Royal Navy captain that revealed a significant contradiction to established history—why the notorious pirate Blackbeard allowed himself to be cornered by surprise by Lt. Maynard at Ocracoke. For that one moment, until a researcher shares their newfound information with the world, they are the only person alive who knows a key fact about the past. And I have been uncommonly blessed to have experienced that sensation on many occasions.

I’ve also traveled, both physically and mentally, to the places where history occurred. This is an essential part of research if a historian aspires to write about past events empathetically and accurately.

I once purposely stood in the blinding rain and deafening surf of a squall on the beach of Hatteras Island where the diminutive lifesaver Rasmus Midgett, in the middle of the night and amid a raging hurricane in 1899, singlehandedly and courageously rescued ten shipwreck survivors from the disintegrating barkentine PRISCILLA.

One day I stood on a grassy, contoured bluff along the caramel-colored waters of Bath Creek as I pondered the mysterious secret of the mythical subterranean tunnel that, instead of leading into the basement of colonial Governor Charles Eden’s palace-like house, led me to the bones and amazing history of Edward Salter, the former pirate-cooper of Queen Anne’s Revenge, who built a church and was the grandfather of three Revolutionary War heroes and a three term governor of Tennessee.

I have sat alone at night at the top of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in the company of the spirit of keeper Augustus C. Thompson, who, in 1886, pressed his body against the exterior of the lantern room wall to keep himself from being tossed over the gallery rail as he bravely rode out the unnerving convulsions, sways, and rumblings of the 20-story unreinforced brick tower during the great Charleston earthquake.

I have explored the ruins of the U.S. Navy’s secret German U-boat tracking station at Ocracoke known as “Loop Shack Hill” and imagined the mixture of its personnel’s tension and boredom as they dutifully, and futilely, stared for hours on end at their fluxmeters, chart recorders, and radio direction finders, in the hopes of detecting and locating a deadly German U-boat lurking offshore.

I have mentally transported myself aboard the crowded lifeboat from the torpedoed passenger-freighter CITY OF NEW YORK on the late hours of Palm Sunday, 1942, being swept into the vast emptiness of the Atlantic by the Gulf Stream, forty miles east of Cape Hatteras, in 25-knot winds and 15-foot seas, chilled in 50-degree air, pitching up and down and drenched by torrents of seawater, as the pregnant 28-year-old Desanka Mohorovic went into labor and gave birth to her son.

For a writer or historian to successfully shape non-fiction history into something someone would want to read, as David McCullough suggests, it is vital for them to achieve this state of immersion as I’ve described. Yet, these seemingly transcendental experiences do not occur magically; they can happen only with a thorough knowledge of the past. This deep mental involvement in past events, and the non-fiction writer’s empathetic “mind’s eye” testimony of history, can only be constructed upon a substantial foundation of research.

Do you have any advice to writers researching history?

Be a skeptic, question everything, don’t assume something is true just because another writer said so. Always remember that there is no such thing as total accuracy or complete truth in writing about the past. All historical interpretations are subjective no matter how well researched. Consequently, good, honest writers must guard against formulating subjective historical interpretations that reflect their personal interests, values, and political, economic or social beliefs. They should not be misguided by their own illusion of knowledge or draw conclusions based on what they want to believe. Writers should challenge their own historical assumptions. The desire of some writers to imprint their point of view on the past makes them vulnerable to the temptation to leap across that perilous chasm that separates historical fact from fancy.

Do you have any books in the works?

I do, a couple of books, but I keep the topics to myself. For me, writing a non-fiction history is a laborious, all-consuming effort. It requires a tremendous commitment of time—writing and editing each day for eight hours or more. When I travel back in time to write a book, I tend to ignore the modern world around me. Life passes the writer by. You have to sacrifice so much in family and social relationships, and your health as well. Writing a book is physically demanding and it takes a toll on one’s health and well-being. I have to weigh these consequences before committing to writing the first sentence. But once I write the first sentence, then, I cannot stop until the book is done.

Do you have a mentor?

My mentors have sadly departed this world. The great pioneering Outer Banks historian David Stick was my mentor and friend, although he once, humorously, tried to convince me not to write books. “There’s no money in it,” he said. Looking back, I am not sorry that I ignored his advice, but he was right. However, money isn’t everything.

As it happens, I’ve suddenly arrived at the point in my life where I am trying to mentor others who are seeking to achieve success researching and writing history.

What has been your longest project and why?

Some projects—more accurately “topics of expertise”—never end. It is a rare gift to have the chance to discover new facts or amend long-established history. Having benefited from such a privilege I’ve come to realize that an independent historian such as myself incurs a debt, an obligation to carry on their role as the caretaker of that story, to continue researching it in order to strengthen its foundation or defend its interpretation. Consequently, a few of my projects or historical specialties are ongoing. I continue to research, analyze, and write about the historic Fresnel lens installed in the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in 1854 nearly 20 years after first publishing “The Lost Light.” I am still researching the identities of Blackbeard the pirate and his inner circle of shipmates 13 years after first publishing that book. It’s a continuous quest for the truth.

Letter written by Confederate quartermaster Capt. George Brown reporting that he had received at Tarboro the entire Fresnel lens taken by Confederates from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in March 1862. Graphic provided by Kevin Duffus.

What has been your most exciting discovery?

My most exciting, most cherished discoveries are the ones that have tangibly altered our knowledge of history and the ones that have overturned longstanding but poorly supported assumptions about the past.

Finding, exploring, and identifying the sunken Confederate gunboat in Chicod Creek when I was 17 years old set me on the path of my 50-year historical odyssey.

Clearly, solving the mystery of the fate of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s historic Fresnel lens will always stand as one of my greatest accomplishments.

Overseeing the solemn reinterment of the skeletal remains of Blackbeard’s cooper Edward Salter at the church he helped to build was a monumental and costly undertaking, but it revealed an unknown, and still under-appreciated chapter of American history.

I am proud to have discovered in 2020 the true facts and architectural pedigree of Charleston’s first lighthouse, the design of which was duplicated for North Carolina’s first lighthouse at Cape Fear completed in 1795. Later that year I discovered the long-unknown identity of the builder of the Cape Fear Lighthouse who died unexpectedly midway during construction.

Following a year-long court case, Kevin Duffus succeeded in establishing the rights of the descendants of the pirate-cooper Edward Salter to have his mortal remains respectfully reinterred at the church that Salter helped to build—St. Thomas Church of Bath, NC. News clipping courtesy of Washington Daily News; photos courtesy of Kevin Duffus.

In 1998, I researched and found the origins and history of Dexter Stetson, builder of both the Cape Hatteras and Bodie Island lighthouses.

While researching my book “War Zone,” I proved why the American WWII pilot Donald Francis Mason of the famous slogan “Sighted Sub Sank Same” did not deserve his hero status and his date with Betty Grable because the U-boat he claimed to have destroyed near Newfoundland was sunk three months later east of Oregon Inlet.

Just recently I presented evidence that proves that Ocracoke Island’s fabled owner William Howard was the oldest pirate in American history.

In fact, within every historical subject I have researched, I have been able to find something new, or correct an assumption that has been misreported. All of these adventures and accomplishments have been exciting, fun, and educational, at least for me.

Who do you admire among historians? Why?

Well, for starters I have looked up to the late David Stick (even though I was a foot taller than he was), the self-proclaimed “maverick historian.” He taught me that it was possible to forge your own path in history and the importance of being a straight shooter—to seek the truth no matter where it leads you and not to fear going against popular institutional doctrine. In general, I admire any historian who does their own primary source research, who doesn’t steal from other historians, and who tells the truth. Not all do.

I also admire historians who can tell a good story. When I was in high school, I was stunned by the writing of Barbara W. Tuchman for her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “The Guns of August,” about the outbreak of World War I. Her book was nothing like the historical writing typical of mind-numbing textbooks. I had no idea that history could be so fascinating.

Other research historians, and philosophers and writers of history who have influenced me include Winston Churchill, C. Behan McCullagh, Nathaniel Philbrick, Michael Gannon, Patrick Pringle, David McCullough, Simon Winchester, Simon Schama, James McPherson, Will Durant, and Joseph Ellis. I am also a big fan of the literary work of Civil War historical novelist Howard Bahr.

You are a good storyteller. Did writing come naturally?

Thank you for saying that. Yes, I would have to say that my writing came naturally but it didn’t come without a lot of self-doubt and hard work. I am entirely self-taught as a writer, storyteller, and as a research historian.

What excites you about history?

Among my favorite writers is the literary naturalist, Loren Eiseley, who wrote: “The door to the past is a strange door. It swings open and things pass through it, but no man can return across that threshold.” On this, however, I disagree with Eiseley. Within our hearts and minds I do believe we have what is necessary to travel back in time, and I have many times.

Finding and solving the mysterious origins of the gunboat in Chicod Creek seven miles west of Washington in 1972 was a watershed event in my life— it altered the course of my life for decades to come.

Who were they, those men who, under great duress, brought that huge, newly constructed vessel up that narrow, winding creek, in the stormy spring of 1862, and scuttled it purposely? Why did they do it? Why, after 110 years, did no one remember what happened? It was then that, in order to search for answers, I first stepped tentatively across that threshold of the door that leads to the past. But what I didn’t realize then, I was at the same time stepping across a gateway to my future.

A letter I found in 1972 among Civil War records confirming the origins of the sunken gunboat, 30 years later became the first clue that set me on the path to one of my greatest historical discoveries—solving the longstanding mystery of the lost Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Fresnel lens.

I see history as a great theatrical stage. The British historian G.M. Trevelyan wrote: “The poetry of history lies in the quasi-miraculous fact that once, on this earth, on this familiar spot of ground, walked other men and women, as actual as we are today, thinking their own thoughts, swayed by their own passions, but now all are gone, one generation vanishing after another…” Simon Schama put it this way: “Historians are left forever chasing shadows… doomed to be forever hailing someone who has just gone around the corner and out of earshot.”

Of course, we all walk in the myriad footsteps of the departed. They call to those of us who will listen. They want us to know the truth of their history, who they were, what they did, why they did it. I think the best historians are able to travel back in time, to see, feel, and experience the events of the past in their minds, and then share those moments of the past with their readers.

How do you define historian?

This is a thorny subject, and my response could invite contempt. I’ll answer it anyway.

Narrowly defined, a historian is generally considered to be someone who has achieved, after many years of study, advanced degrees from schools of higher learning and who has pursued a career as an academic, published professional. Like my late friend David Stick, I am not one of them.

I only call myself a historian to avoid lengthy, awkward explanations like this one. I know that there are graduates of history programs who dislike it when people like me refer to themselves as historians. Encouraged by their professors, they often describe those of us who research and write history without advanced degrees pejoratively as “simply journalists.” This, despite the unfortunate fact that many graduates of history programs today are not gainfully employed as historians.

On the other hand, the term historian has today become used rather loosely to describe just about anybody who presents themselves as an authority on a historical subject, even if their expertise was only acquired by reading a few books. It seems like anybody can be a historian these days.

Was David Stick simply a journalist? I’ll leave that for others to decide. As for me, for the past 25 years, I have done nothing but research history, produce documentary films on history (five), write books (six) and articles (dozens) on history, present lectures on history (nearly 1,000), and share my passion for history everywhere I go. I’ve even made a little money along the way so I suppose that classifies me as a sort of professional historian even if that may annoy some academic historians.

What are you goals as a writer, researcher, and historian?

Beyond what I’ve already said about historical truth and my aspirations for literary quality in historical writing, I would add that it is my highest goal to inspire and guide future historians and ignite a passion for history in others. I truly fear for the preservation of our history and the well-being of future generations who will continue to diminish or entirely cancel the importance of knowing our history.

“One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil must be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over,” wrote the eloquent African American historian W. E. B. Du Bois. “The difficulty, of course, with this philosophy is that history loses its value as an incentive and an example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth.”

Other notable public figures have addressed this issue, including President John F. Kennedy, but I will offer three more quotations that, in my mind, best characterize the value of knowing one’s history.

British philosopher Anthony O’Hear expressed it as well as anyone: “We are depriving our children of knowledge of the history that has made us what we are, in our futile efforts to be modern. In the process, we are forging a new dark age. Is it any wonder that, with no sense of our past or identity we are a culture obsessed with celebrity, football, and reality television? To be ignorant of the past is to make us impotent and unprepared before the present.”

British historian Sir Michael Howard stated why it is imperative that a nation’s leaders must have a thorough grasp of history: “People often of masterful intelligence, trained usually in law or economics or perhaps in political science, have led their governments into disastrous decisions and miscalculations because they have no awareness whatever of the historical background, the cultural universe, of the foreign societies with which they have to deal.” Nowhere does that apply better than the West’s failures to manipulate the Middle East.

Lastly, I will quote these words of Simon Schama: “History ought never to be confused with nostalgia. It’s written not to revere the dead, but to inspire the living. It is part of our cultural bloodstream, the secret of who we are. And it tells us to let go of the past, even as we honor it; to lament what ought to be lamented; and to celebrate what should be celebrated.”

Between 1984 and 1987, Kevin Duffus served as Executive Producer of state-wide television coverage of North Carolina’s 400th Anniversary. In this photo taken on the Barbican pier where Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe departed in 1584 for a reconnaissance expedition to the Outer Banks, Duffus directs a news report by WRAL-TV news anchor Charlie Gaddy. Photo by Neil Kuvin provided by Kevin Duffus.

When did you start writing?

Probably, the first time I did any serious creative writing was in high school. My first career was in television and as a producer I had to write documentaries, but it didn’t come easily. I had absolutely no training. And TV writing is not particularly high-level work. My writing has developed along the way. I’m sometimes asked for advice on writing and my answer is a common one—read good writers and only good writers on a daily basis. I aspire to achieve literary non-fiction as a writer, so I seek those types of books.

Did you read a lot as a child?

I did when my mother made me. She made us read to each other, often Dickens, and now five decades later I realize (and appreciate) what she was up to. I did spend a lot of time reading the World Book Encyclopedia and National Geographic Magazines as well.

What thrills you about life?

Learning new things—mostly about those people and events that have preceded us and the lessons we can derive from past. Perhaps, more than anything, I am currently fascinated by turns of fate, those seemingly inconsequential moments and choices in life that dramatically alter someone’s future. I have been doing intensive genealogical research into my ancestors who lived and worked in the 19th century in lower Manhattan—my 16 great-great grandparents whose life’s paths, serendipitously brought them together to produce my very being. I find that thrilling, mysterious, miraculous, and endlessly intriguing.

Personally, I have identified five pivotal inflection points in my life that set in motion a chain of events that brought me to this very moment in time as I am writing this answer to your question. Sometimes these consequential turning points are the result of external influences; other times they are the outcome of our own choices. Except for our own family members, everyone we meet and/or become friends within our lifetimes is the result of a choice we made somewhere in the past. And so is history made.